HEADING HOME - PART ONE

NEW DELHI

(For the full story read The Gainesville Years, 1 through 14)

I came to Bangladesh alone a week ahead of the film crew to do my research and begin writing the shooting script. Now it was time for me to leave—alone. The crew still needed to pick up some shots to complete the story, but I had to get back to the university. The fall term was just a couple weeks away and I needed time to prepare for the two news writing labs I would be teaching.I had a choice of routes: through Hong Kong or through New Delhi. There were unbelievably good shopping bargains to be had in Hong Kong, I was told, but no matter how good the bargains, I didn’t have the discretionary funds to take advantage of them. However that wasn’t the only reason I chose to return to the States by way of New Delhi.

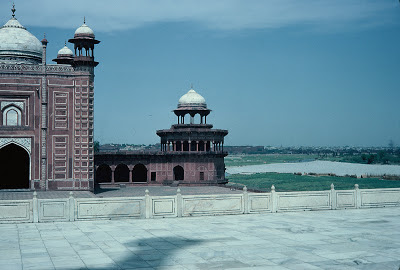

When I was a young, romantically inclined teenager I came across an issue of the National Geographic Magazine that extolled the wonders of a magnificent building, one of the Seven Wonders of the World. It was not just the beauty of the structure that struck me, but the story behind it. That building was the Taj Mahal, and the story was about an Indian prince who was so aggrieved by the death of his favorite wife that he built this remarkable, unbelievably beautiful structure as a tribute to her and a testament to his love.

As a teenager I was moved by this tale; as an adult it still held sway over me...but I never dreamed I would one day get the chance to see the exquisite architectural work of art it inspired. I may never have an opportunity like this again, I told myself. Putting my financial insecurity temporarily on hold, I decided to layover in New Delhi for a couple days on my way home, and take a side trip to Agra to see this sacred tribute to undying love.

Not widely traveled at this stage of my life, I asked our travel agent to avoid hotels usually frequented by Americans and book me into a place that would give me a real sense of the country. I wanted to “experience” India. In theory this sounded like a good idea. It never occurred to me that I would be isolating myself; that I would be eliminating any chance for the kind of camaraderie that often blossoms among tourists from similar cultures traveling abroad--a particularly desirable option for someone traveling alone.

There was one challenge my decision to make this short trip alone created that I had not expected. It is probably no longer true, but 35 years ago there was a prevailing concept in India that all Americans were rich. A rich American woman traveling alone, which was, of course, how I was perceived, was a magnet for sidewalk venders eager to sell her their little piece of India to take home. When I attempted to do a little sightseeing on foot they descended on me, all smiles, beseeching me to inspect their wares. I rejected their offer as graciously as I could, and sometimes this worked. But sometimes the men would turn hostel, nasty. They seemed to take my rejection personally. So I stopped walking out on my own.

And then there was my cab ride from the airport. The cab driver was friendly enough—too friendly. Once he realized I was traveling alone, he turned on the charm. At first it seemed like just an over-earnest sales pitch. He wanted me to hire him for the duration my stay. He would be happy to show me around. Something about his effusive manner made me uncomfortable. I thanked him, but declined. That is when he really turned on the charm.

He produced some letters, ostensibly recommendation from satisfied “American Women” who had used his services. The fact that he kept turning around to talk to me while wending his way through the city’s chaotic traffic did little to advance his cause. Nor did his not so subtle flirtatious remarks and suggestive references to the other services he could provide beyond that of tour guide. In hindsight, I doubt he was talking about sexual benefits. He was probably just attempting to be charming. But at the time it made me very uncomfortable. And the more he talked, the more uncomfortable I became.

I made arrangements with the hotel to purchase a train ticket for me to Agra. In the meantime, I wanted to see a bit of New Delhi. The desk clerk found a driver for me who turned out to be remarkable. It wasn’t just that he provided me with an excellent overview of the city, and seemed very knowledgeable about all of the places he showed me. What I found remarkable was the fact that we were three quarters of the way through our tour, with me chatting away, with him nodding and smiling… before I realized he didn’t understand a word I was saying. When the hotel clerk said this cab driver spoke English…he meant that he could tell me about the sites in English—apparently a script he had memorized. My driver didn’t actually speak or really understand English. But it was a great tour, and he was a pleasant chap. I laughed at myself for taking so long to catch on, but I thoroughly enjoyed the day.

|

| One of my favorite sites in New Delhi was the Laxminarayan Temple. Another view of The Laxminarayan Temple |

As he showed me around the temple, the young man explained that Hinduism, one of the world's oldest religions, has many forms. It is an inclusive religion that respects other religions, and over the centuries, as in the case of Buddhism, has sometimes incorporated the wisdom and moral teachings of other faiths.

The main temple is spread over 7.5 beautifully landscaped acres and houses statues of Lord Narayan and Hindu Goddess Lakshmi. (Thus, the temple's name.) There are other small shrines dedicated to Lord Shiva, Lord Ganesha and Hanuman. And, to bear out what my guide had told me, there is also a shrine dedicated to Lord Buddha. The left side temple shikhar (dome) houses Devi Durga, the Hindu goddess of Shakti, the power.

Later that afternoon we drove into "Old Delhi" and my driver pointed out the Red Fort. He told me that they had evening light shows during which the history of the Fort is dramatically told. There would be an English version presented that night. When we got back to the hotel I asked the desk clerk to purchase a ticket and arrange for a cab to take me.

|

| The Red Fort is shaped like an octagon, and covers over 254 acres. It derives its name from the extensive use of red sandstone on the massive walls that surround the fort. |

At some point it must have become apparent that "the rich American Lady" wasn't going to buy anything, or even stop to inspect their wares. I felt the mood change. The men's gracious facade disappeared. In its place I sensed a subtle hostility. I didn't need to understand the language to realize they were talking about me: the unflattering pantomime exaggerating my walk, the sarcastic tone of a comment that triggered laughter.

Once within the Fort's walls, as the light show began, the discomfort I was feeling outside vanished.

I became completely caught up in the experience. It was astonishing. The history of the fort unfolded in beautiful, music-accompanied prose. Colored lights brushed the walls and alcoves, highlighting the areas that were the historic backdrop for the story being told, and bringing the saga to life. While I have no pictures from the light show, here are some views of the Red Fort.

When the light show ended I exited with the crowd. As instructed by my cab driver, I headed to where he had dropped me off . He said I would be able to get a cab there to take me back to my hotel. As soon as I was outside the discomfort I felt earlier returned. It was dark now. The merchants were gone, but there were still men lingering along the street. I tried to stay close to the group. It might have been my imagination, or the hour, but I felt as if I was being watched by hostile eyes.

I finally reached the cab stand and, giving the dispatcher the name of my hotel, requested a cab. He mumbled something I did not understand, and motioned me aside, then quickly ushered the couple who had been behind me into the waiting cab. I tried again, and again he motioned me aside, admonishing me to be patient as he hustled another group into a waiting cab. I watched as each couple or group and even a few single men were dispatched; I watched as the number of waiting cabs dwindled. Finally out of patience…and frankly, more than a little scared as the area emptied and the Fort’s exterior lights were shut off... I demanded that the dispatcher put me in a cab. He ignored me as he put the last couple into the last waiting cab.

“Are there more cabs coming,” I asked. “No” he replied. I panicked. “How will I get back to my hotel?” “I told you, Lady" he said,"I told before... none of the cabs will take you. Your hotel is too close. You must take that.” He pointed across the street to a bicycle-powered rickshaw. I know now that I should have matched my request for a cab with some rupees, but I didn't understand Indian economics then.

|

| These rickshaws are in Dhaka, but they are like the rickshaw I took back to the hotel that night from the Red Fort |

Defeated, I crossed the street and engaged the rather seedy, underfed young man who was standing next to the rickshaw to take me to my hotel. We moved at a snail’s pace through the dark streets. It seemed like an eternity before we reached the hotel, and I was charged double what I had paid the cab that took me to the Fort. Still I have no regrets. For a couple hours that evening I stepped back in time, into another India. An India that was vibrant, opulent. Filled with violence, perhaps, but an India where poets were as honored as warriors, and where princes made war, but also created beauty...remnants of which are still with us today.

The main reason I had come to New Delhi was to see the Taj Mahal, but even with the help of the hotel staff, I was unable to purchase the necessary train ticket to Agra. The clerk was apologetic. It was tourist season. There were just no train tickets left in my time frame. I was heartbroken. Then a miracle: The clerk mentioned my plight to a Pakistani couple staying at the hotel who, happily, spoke English. The man was attached to Pakistan's diplomatic service. They too wanted to visit the Taj Mahal and were unable to get train tickets to Agra, so they had arranged to rent a car. And if I wished, I could share it with them.

Next: The Taj Mahal--The final installment of my Bangladesh-New Delhi adventures