BANGLADESH, THE CREW ARRIVES

The crew finally arrived in Dacca. Much to my delight, it included another woman—a first (and as it turned out, the last) in all my years of doing this work. Today women can be found in all aspects of film making, but thirty-five years ago you would have been hard pressed to find a woman in a technical crew position state-side, let alone on an overseas assignment. Her name was Fran Tarranella. She was a bright, ambitious twenty-something sound engineer out of Atlanta.

|

| Crew conference before hitting the road.. |

Unlike documentary makers who have the luxury of spending a year or more finding their story, we were on a tight, fixed budget which dictated that we complete all our shooting in roughly two weeks. So, with a number of locations slated for filming, in the early hours of the morning the day after they arrived, our small crew, which, besides Fran and me, included our producer, Sandy McDonnell , our director, Neil Halslop, and our cinematographer, Mitchell Lipsiner... along with a missionary who would serve as our translator and guide... piled into a car and hit the road.

Years traveling with all-male film crews overseas and in remote areas of the United States where amenities are few and far between, prompted me to develop a well-disciplined bladder, something Fran had not yet done. After about two hours on the road she informed Sandy that she was in need of a rest stop.

We pulled into a gas station and Sandy asked the owner for permission to use the rest room. Permission was granted—until the man, a devout Muslim, realized that the request was for a woman. The offer was immediately rescinded by the angered proprietor, who was offended by the request. From what we could gather from our guide and translator, the owner considered the request an insult since women were unclean. Allowing one to use his “facility” would be a desecration. Her use would somehow contaminate it. No man would ever be able to use it again. Our missionary guide apologized, but said there was no use trying another place. In this Muslim area we would get the same reception everywhere.

In the end, whenever we were on the road, a clump of bushes a respectable distance off the highway had to suffice as a ladies room for Fran and, on occasion, me, whenever we required one.

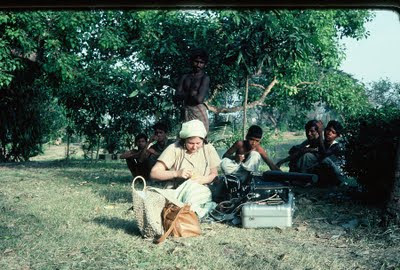

Then there was the amusing clash of culture Fran unwittingly ran into in a little Hindu village.

Fran carried her recording equipment slung over her shoulder and leaning on her hip, much like the women in the village transported their young children. A man carrying his equipment in such a manner would have attracted little attention, but a woman, wearing pants (permissible when we worked in Hindu communities), with a large machine strapped over her shoulder in that manner—stirred up considerable curiosity and conjecture. Just how much, I discovered as I was prepping some of the village women for some shots we wanted of them going about their daily chores.

In an effort to build rapport with them, I searched for common experiences. Since child bearing and rearing were the core of village life for women, that is what we discussed. They were delighted to learn that I had children, and that two of my children were sons. In Bangladesh, the more sons a woman has, the higher her status. There was a practical reason for this hierarchy.

In the villages of Bangladesh, when a woman marries she joins her husband’s family and becomes a virtual slave to her husband and mother-in-law, to whom she must show the greatest respect. If the woman has only daughters, she never rises from this lowly position. But if she has sons, eventually she becomes the matriarch in her son’s household. Without sons, if her husband dies, she has no place to go. Ergo, the more sons, the more security and the more power.

|

| Gettinhg ready to record |

“What did she say?” I asked.

“Oh,” my translator said, laughing herself, “she has figured out that your friend does have a child. It is that thing she carries on her hip and is always talking to.”

I looked over at Fran. She was doing a sound check, talking into her equipment. She did, indeed, carry her equipment around much like a village woman would carry a child. She treated her equipment gently, carefully, and did talk into it softly as a mother would talk to a child. In a way, I guess, her equipment was her “child.” At least, that’s how the women in the village saw the situation.

|

| Fran at work |

|

| Making friends |

|

| Madonna, Bangladesh style |

|

| Dinner prepaaration |

|

| Bath Time in a Bengali village |

NEXT: MORE STORIES FROM THE ROAD