We don’t mature in an even pattern, but rather through unexpected spurts of sudden awareness; those eureka moments when something unpredictable happens that challenges our perception of who we are and the world we inhabit. I had a series of such experiences in 1972 during an assignment in Brazil—a trip that changed the way I see myself and my world.

Forty-two, and at the top of my game...I thought

I was 42 at the time. The forties are a great time in a woman’s life. Gone are the insecurities of her twenties and the desperation she feels to succeed that mar her thirties. At least that is how it was for me. While I had not planned to have a career, as was the case for many women of my generation, marriage didn’t turn out to be exactly what I anticipated. Working was not an option; it was a necessity.

Fortunately, I landed in a career I enjoyed, one that enabled me to sustain my role as mother, though that did take a bit of maneuvering at times. I was feeling pretty confident about the way I was handling my life and the progress I was making in my career. When I was approached with an opportunity to go to Brazil to write and field produce a film project for the Presbyterian Church U.S. I didn’t think twice about it. Not until I was on the plane headed for Brazil.

There had been no time to think about it before then. Arrangements had to be made for the care of my three children while I was away. I had assignments to finish and clients to notify because the job was going to take me out of the country for nearly a month. And there was the research. We knew the film would be used to raise money for a certain ministry in Brazil, but no one—not the Church or the film company—knew what we would be filming. That was what I was being sent in advance to determine. The only thing I did know was that we would be spending most of our time in the interior, and I wanted to learn something about the area before I got there. Remember, this was in the days before the internet, when research was a hands-on process in a library, or required writing letters or making phone calls to get the information you needed.

The first thing I learned from my research was that I had been wasting my time brushing up on my Spanish. Brazilians speak Portuguese. Equally disturbing was the fact that much of the information I found about the area compared it to the American Wild West. According to one of my resources:

"A trip (into the interior) can be dangerous due to the presence of wild animals including ferocious spotted jaguars and poisonous snakes, and also road bandits. Travelers are cautioned to carry a rifle in their vehicle, as well as their own supplies as there are no hotels, gasoline stations or restaurants along the highway.”

But it wasn’t until I heard the wheels snap up under the plane and saw Miami shrink below its wings that it fully dawned on me: What in God’s name was I doing! I was no world traveler. In fact, I had never been out of the country. And now here I was on my way to meet a man I did not know...to travel into the rugged and apparently dangerous interior of a country I knew nothing about...where the people spoke a language I did not understand.

My concerns were compounded when we finally touched down in Fortaleza eighteen hours later and I met my greeting-party-of-one. I spotted him as I exited customs—tall, gaunt, slightly bent, with thinning grey hair, holding up a hand-printed sign with my name on it. Looking back, I realize he could not have been more than 60, but to the 42 year old I was then, he looked ancient...and frail. Not up to the rigors I expected we would be encountering on our shoot in the untamed interior of this country.

“Reverend Mosely?” I asked, half hoping I was wrong. The man could have, after all, just been a messenger sent to fetch me. No such luck.

“Bill, call me Bill,” he said as he relieved me of my suitcase. That’s when I noticed the eyes. The face was drawn, tired—old, but there was something about his blue-grey eyes. In spite of his serious demeanor, I’d swear his eyes were laughing. It was disconcerting, but somehow made me feel more at ease. Not for long, however.

Bill whisked me off to his house in what I would have to call a less than respectable part of the city. Lest I miss it, as we got out of the car he pointed across the street to a “gentleman” zipping up his fly as he exited one of the rooms in what looked like a run down, two-story motel. I thought I detected a flash of mischief in those laughing eyes as Bill apologized for the neighborhood. “Missionaries don’t get much of a stipend to live on, you know” he said. “The money doesn’t go far in a city like Fortaleza. We live where we can afford to.”

The plane ride had been long and I was tired, but as soon as we entered the house Bill told me to hurry and freshen up because our ride to Estreito would be there any moment. Estreito was a small settlement in the interior close to the Amazon River. It was where, Bill said, I would be conducting my first interviews. Bill was concerned that we get on the road as quickly as possible because it was a long drive, and he wanted to get to the half-way point before dark—a Baptist Mission where we could safely spend the night.

As it turned out the sun had already begun to set by the time Milton Calvacente finally showed up. Milton was one of the Christians involved in the project that was to be the subject of our film, one of a small group of Brazilian Presbyterians who, with the help of donations from churches in the United States, were rescuing starving families from Brazil’s drought-plagued sertão. (Portuguese for back country or backlands.)

Milton was in Fortaleza to pick up a used truck for the group’s work. Bill and I were going to hitch a ride with him into the interior. Unfortunately there were some problems with the truck which had to be fixed before we could get on the road—news that did little to temper my nervousness about the trip.

The vehicle’s interior only had room for the driver and one other person. Insisting I ride inside, Bill climbed into the bed of the truck, where he had already stowed our suitcases and some supplies for the settlement. I was uncomfortable with the idea, still deluded that the missionary was frail and the ride would be too rough on him. I had no idea, as we headed out of Fortaleza towards the Belém-Brasília Highway—or as it is known in Brazil, Rodovia Belém-Brasília—just how rough the trip that lay ahead of us would be.

Coming from the United States, the word “highway” conjured up for me the vision of a paved four or six lane road. Not so in the Brazil of 1972. Shortly after we left Fortaleza we found ourselves on a crowded, badly rutted two-lane dirt thoroughfare. Crowded because the condition of the road caused many of the trucks that traveled it to stall or get stuck, backing traffic up for miles behind them. Negotiating the Belém-Brasília Highway back then was a stop and start process.

Backup on Rodovia Belém-Brasília, 1974

There was an upside to the slowed pace: The shocks on the truck were not very good. At that slower pace we didn't feel the bumps as intently.

Bill Mosely (in truck) and friends

Since Milton spoke no English and I spoke no Portuguese, about all we could do was smile at each other...which we did frequently. About an hour into the trip a terrible thought went through my mind. What if something happened to Bill? As I said, he seemed old and frail to me. What if he died while we were in the interior? He had warned me that no one spoke English where we were going. How would I manage if something happened to him? How would I communicate? I tried not to think about the possibility.

Probably out of boredom, Milton began singing. I didn’t understand the words, but I recognized the melody: “You Are My Sunshine.” I joined in...in English of course.

Now I have to pause here a moment to explain what a desperate move that was for me. I love music, but singing is not something I do in public, especially in front of strangers. My ex-husband used to joke that I shouldn’t sing to our children or I might make then tone deaf. The truth is the only course I ever came close to flunking was a college course in elementary education (before I realized I didn’t want to be a teacher) in which I had to sing a simple children’s song without accompaniment. I didn’t even come close to getting the melody right. But on that dusty disaster of a road, stuck in a truck with a man who spoke no English, I was desperate to find some way to communicate. Singing was all I had.

We went through a number of other songs, mostly folk tunes, and a couple of American pop classics that apparently sustained their appeal south of the border. This went on for the next hour or so —me providing the English and Milton (whose voice was quite pleasant) singing in Portuguese. It was a hit or miss process. He would start a song. If I recognized it I would join in (or fake it, if I didn’t know all the lyrics). Milton seemed to have some favorites which we repeated until we were finally all “sung out” and lapsed back into silence.

We drove along until we hit another back-up. Milton would stop. Sometimes we would get out and stretch our legs. Other times we would just sit and wait until the traffic started up again. It was almost dark when, during one of our stops, Bill tapped on the window and motioned for Milton to get out. The two of them held a brief conference, and then Bill came to my window.

“Were not going to make it to the mission tonight,” he said. “Milton tells me there is a settlement down the road that rents rooms. We’ll stop there.”

A little further down the highway Milton turned off on to a narrow dirt road. By this time it was completely dark. We came to a cluster of ramshackle structures that looked much like a movie set for an old western. Milton pulled in and he and Bill got out of the truck.

"You stay put and lock the doors," Bill said. "Milton and I will check and see if they have a room. We'll all stay together tonight... just to be safe."

I searched his face for some sign that he was kidding, but there was none. As they head down the path I locked the doors and crunched down in my seat.

The night was quiet. There was no moon. An oil lantern lit part of the narrow lane, casting shadows everywhere. Suddenly I was aware of two shapes in the shadows. Two men emerged into the light; one was a dead ringer for Poncho Villa, handlebar- mustache and all. Both were wearing sombreros... and guns. As they passed in front of the truck, the one who looked like Poncho Villa peered in and grinned at me, revealing the absence of his two front teeth. I flashed him a weak smile, and held my breath. He turned and said something to his companion. They both laughed and moved on. I exhaled.

It seemed like an eternity before Bill and Milton returned. “We’re not staying here,” Bill said as Milton got behind the wheel. There’s another place a few miles down the road... it will be better.” Bill climbed into the bed of truck and Milton pulled out and headed back to the highway.

A few minutes later we turned off the highway again and snaked our way down another dark jungle road until we reached a cluster of buildings. Again I was told to wait in the truck and keep the doors locked. And again it seemed like an eternity before Bill and Milton returned. But this time there was a smile on Bill’s face.

“This will do just fine,” he said, opening my door. Bill and Milton grabbed our suitcases and the three of us followed the path into a dark courtyard. We were joined by a slight built man in a pair of khaki pants and a sports shirt—a far cry from the unsavory looking characters I had encountered while waiting for Bill and Milton at the last settlement. He led us by candle light across the courtyard to a doorway, unlocked the door and pushed it open. The man exchanged some words with Bill in Portuguese, then reached into his pants pocket and pulled out a two or three inch remnant of a candle, lit it from his own candle, and handed it to me.

“Go on in,” Bill said.

I crossed the threshold. The oppressive heat sucked the breath out of me. The room was small and almost square. In the light of my candle I could make out a single cot shrouded in mosquito netting, and a small unfinished wood table.

“There should be a holder for your candle on the table,” Bill said.

There was--a saucer shaped punched tin candle holder. I looked over at the pane-less window which had been secured by a panel made of mismatched boards nailed together. It looked as though it opened outward. Bill must have read my mind. “Don’t open the window,” he called. “The mosquitoes will eat you alive.” He placed my suitcase inside the door. “We’ll see you in the morning,”

I panicked. “I thought you said we were going to stay together.”

“You’ll be fine,” Bill said. “This place is okay. Get some sleep. We still have a long ride ahead of us.” With that Bill closed the door. I experienced a moment of sheer terror. I had to pull myself together. Bill wouldn’t have left me alone if he didn’t know it was safe, I told myself. I placed the candle into the holder, fetched my suitcase and started to open it. What was I doing? There was no way I was going to get into my pajamas...no way I was going to take off my clothes. I put the suitcase aside, lifted the mosquito netting and lay down on the cot. There was no way I was going to sleep either.

I lay there on the cot and watched the candle burn down, sputter, and go out... leaving the room in complete darkness. What time was it? I squinted at the face of my watch, but it was no use. I couldn't see a thing.Why hadn’t I thought to bring a flashlight?

I won’t swear that I didn’t dose off now and then. I know how easy it is to be unaware of those short respites of sleep in an otherwise sleepless night. But it seemed like I didn’t. Then the roosters started. Being a city girl, I thought roosters only crowed at dawn. Not so, at least not in the Amazon. The crowing went on intermittently all through the night.

Laying there on the cot, fully dressed, breathing in the stale air, I waited impatiently for morning to come-- not that I would be able to tell when it did, cloistered as I was in that pitch black, oppressively hot little room. And I certainly had no intention of opening that door to find out. Instead I fretted over what might be on the other side: wild animals; poisonous snakes; blood-sucking, malaria-carrying mosquitoes—bandits.

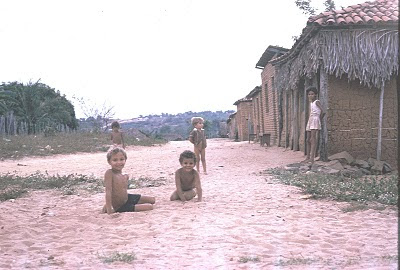

Eventually the morning came. There was a knock on my door. I cracked it open. It was almost as though I had gone to bed in one world and awoken in another. The ominous shadows of the night before that, in my imagination, hid all kinds of dangers were gone. Sunlight filled the courtyard, which was now filled with women chatting as they went about their morning chores, and children laughing and playing. And the few men passing through looked--well, as normal and friendly as Milton.

My accomodations my first night in Brazil, by morning light

As I grabbed my suitcase and followed Bill to the truck I made a mental note to myself: An imagination is a necessary thing for a writer, but this was the last time--on this trip--that I was going to let it run away with me.