Thursday, November 4, 2010

Post script on Gainesville Years

Some things in life come back to haunt you, but if you are lucky, some things come back to make you kvell. (For those of you unfamiliar with this Yiddish word that has no English counterpart... it is from the German quellen, and the closest translation I can give you is to swell with pride, or gush.). I had such a kvelling experience recently. It involved something I did 35 years ago while teaching at the University of Florida.

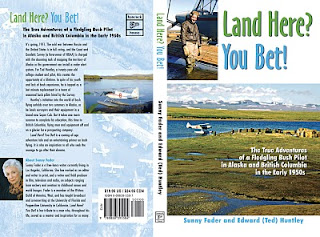

Recently two of my essays were published in Slices of Life, a collection of short fiction and essays published by the Florida Writers Association (FWA) in conjunction with Peppertree Press. The book was released during the FWA conference on October 22, 2010 in Orlando, Florida.

At a book signing for the authors, I asked the “person of renown,” the published author who was chosen to pick the top ten stories from those accepted for the collection, to sign my book. The young man, Elliot Kleinberg, is a journalist with ten published books to his credit. The conversation went something like this.

Kleinberg: You are the Sunny Fader who taught at the University of Florida, aren’t you?

Me: Yes, I am.

Kleinberg: You don’t remember me, do you?

Me: (Embarrassed ) No. I’m Sorry.

Kleinberg: I was one of your students.

Not only was he one of my students, but he told me, and a number of other people at the conference, that most of what he learned about writing he learned from me, and I was the reason he went into journalism and became a writer.

There is probably no greater "high" than learning, first hand, that something you did made a positive difference in someone's life. Elliott (that's him towering over me during the conference) said he enjoyed my broadcast writing class so much, after graduation he went into broadcasting. However, it was the writing aspect he enjoyed most, so eventually he became a newspaperman and nonfiction author. I confided in him that, even though I spent most of my life in television, it is the writing I love most too... and now that I have the luxury of pursuing that passion, I am writing essays and books.

I have heard from a couple other former students I have led (or misled) into a career in the entertainment or journalism industry: Jack Herman, also a former UF student of mine, followed me to Hollywood and is still there, working in "the industry." And recently I heard from Lisa Hackett (Buddy Hacket's daughter), who was a student of mine at Pepperdine University, and now has her own production company. If there are any other former students of mine out there who happen to come across this blog, I would love to hear from you. On Facebook, or you can email me at sunnyfader@tampabay.rr.com.

Recently two of my essays were published in Slices of Life, a collection of short fiction and essays published by the Florida Writers Association (FWA) in conjunction with Peppertree Press. The book was released during the FWA conference on October 22, 2010 in Orlando, Florida.

At a book signing for the authors, I asked the “person of renown,” the published author who was chosen to pick the top ten stories from those accepted for the collection, to sign my book. The young man, Elliot Kleinberg, is a journalist with ten published books to his credit. The conversation went something like this.

Kleinberg: You are the Sunny Fader who taught at the University of Florida, aren’t you?

Me: Yes, I am.

Kleinberg: You don’t remember me, do you?

Me: (Embarrassed ) No. I’m Sorry.

Kleinberg: I was one of your students.

Not only was he one of my students, but he told me, and a number of other people at the conference, that most of what he learned about writing he learned from me, and I was the reason he went into journalism and became a writer.

There is probably no greater "high" than learning, first hand, that something you did made a positive difference in someone's life. Elliott (that's him towering over me during the conference) said he enjoyed my broadcast writing class so much, after graduation he went into broadcasting. However, it was the writing aspect he enjoyed most, so eventually he became a newspaperman and nonfiction author. I confided in him that, even though I spent most of my life in television, it is the writing I love most too... and now that I have the luxury of pursuing that passion, I am writing essays and books.

I have heard from a couple other former students I have led (or misled) into a career in the entertainment or journalism industry: Jack Herman, also a former UF student of mine, followed me to Hollywood and is still there, working in "the industry." And recently I heard from Lisa Hackett (Buddy Hacket's daughter), who was a student of mine at Pepperdine University, and now has her own production company. If there are any other former students of mine out there who happen to come across this blog, I would love to hear from you. On Facebook, or you can email me at sunnyfader@tampabay.rr.com.

Monday, August 30, 2010

THE GAINESVILLE YEARS, PART 3

BECOMING A SCREENWRITER – THE HARD WAY

It took a couple weeks, but eventually I settled into the semester. As time passed I became more comfortable in my role as an instructor. It was fun to work with the energetic young men and women who streamed into my lab three afternoons a week to soak up what they perceived (rightly or wrongly) as the wisdom and experience I brought to the course.

They were an eager bunch, determined to learn the critical skills they needed to fulfill their dreams of becoming media stars. That is what they all wanted, you know; not just to become broadcast journalists, but stars like Connie Chung, a young TV news woman who was all the rage at the time, or Dan Rather, then one of the fair-haired boys of television news. They all knew who Rather was because he made frequent visits to the university to see his former instructor and mentor, now the head of University of Florida’s Journalism Department.

One bright-eyed young woman asked me if I thought she should take drama classes to improve her presentation skills. I am afraid I left her somewhat dismayed when I recommended instead that she pick up some courses in history and geography so she would at least know what she was talking about when she read the news on-air.

As for my private life—it was flourishing. Within a matter of weeks I found myself with a supportive circle of new friends. Someone was always asking me to dinner or inviting me to attend a get-together of some kind. One of my new friends, Joy Anderson, a children’s book author who taught children’s literature in the English Department, brought me into a group of professors from different disciplines who met once a month to gain a broader perspective of what was going on at the university. It is easy to become isolated and myopic when your time is spent exclusively with colleagues in your own discipline. A bit of inter-department pollination breeds a sharper mind, and a more content soul.

Once I felt secure in my teaching abilities, I looked to the school’s affiliated public radio and TV stations for more challenges. Dr. Christiansen assigned me the task of writing promotional announcements for both stations, a responsibility that gave me a chance to use skills I had developed early in my career when I was the Assistant Promotional Director for WCAU TV in Philadelphia. What I was really hoping for was on-air work; radio or TV, I didn’t care. However, all the spots were already filled by other faculty, and they were very protective of those assignments.

Then one day, I got my break. I had just sent Eileen off to school, placed two eggs in boiling water and was about to set the timer for four minutes, when the phone rang. It was the TV station manager.

“Sunny, can you get down to the station right away. Dr. Jacobson is sick, and we have a writer coming in in just a few minutes for an on-air interview, and no one available to do it.” I didn’t have to be asked twice. I was out the door in a flash.

I reached the studio just as we were due to go on the air; there was no time to prep for the interview. Fortunately, Dr. Jacobson had left his notes at the station and I had a chance to glance at them as I took my place. This gave me enough information to get the conversation started. I played off the author’s answers for the rest of my questions. Everyone, including the author, seemed to think the interview went well, which put me in high spirits for the rest of the day—until I spoke with my daughter.

There was a note on my desk when I returned to my office that afternoon after class: “Your daughter wants you to call her right away. She said it’s urgent!” All those instinctive fears that come with motherhood kicked in. They were exacerbated the minute I heard Eileen’s voice.

“Whoa, slow down,” I said. “What stinks?”

“The kitchen...the kitchen stinks,” she yelled into the phone. “and the whole apartment.. And there’s stuff all over the stove, and the ceiling. It’s gross! What did you do?”

At first her words didn’t compute; then it hit me. “Oh my God, the eggs! I forgot to shut off the stove.”

Eileen raved on: “And there’s a big hole in the bottom of the pot, and its stuck to the stove. It’s ruined. Everything’s ruined. You’ve got to come home right now!”

I had hoped my daughter was exaggerating—she was prone to drama—but she wasn’t. The apartment did stink. The acrid odor of sulfur hit me even before I opened the door. When the water in the pot evaporated the eggs had exploded, splattering the ceiling and wall with a malodorous hard yellow, white and brown residue. In my daughter’s words, it was “gross.” It took me two hours to clean everything up, and much longer before the unpleasant odor finally faded.

“You could have burned the place down, Mom.” Eileen was cross with me, not just because of what I did (or, actually, didn’t do), but because she was the one, not me, who came home to discover it. To save face, I insisted that she was being over-dramatic, but I knew she was right. I was lucky my carelessness had only created a mess. It could have created a tragedy.

After the egg incident things settled down again between Eileen and me, and I reclaimed my role as parent—well almost. She still occasionally confused our roles, like when I would go to spend an evening with friends and promise to be home around ten. Inevitably, at ten o’clock on the dot, no matter where I was, the phone would ring. “Has my mother left yet?” the young authoritative and slightly ‘pissed’ voice on the other end of the line would ask. It got to be a running joke among my friends. No gathering was considered complete until Eileen called.

The fall semester was about four weeks away when Dr. Christiansen called me into his office. “I have a new assignment for you,” he announced. “You will still teach the news writing lab, but a number of students have requested that we add a screenwriting course next semester, and I want you to take that class too.”

“I don’t know anything about screenwriting,” I protested.

“You write scripts for documentaries,” he said.

“Yes, but that’s not the same thing.”

“Well,” he said, “it makes you more of an authority on writing for film than any other members of the faculty, so you’ll do the class. See if you can put something together by next week.”

I had been nervous about teaching broadcast writing, but at least I had people I could turn to for help. The prospect of teaching screenwriting petrified me, particularly after Dr. Christiansen designated me the department’s prime authority on the subject. This was, remember, in the days before Syd Field and a flood of other “experts” began glutting the market with books about screenwriting.

I wrote to studios and TV stations asking if they could send me some old scripts to use for the new course. (I didn’t know about the Writers Guild of America in those days.) I scoured the library for books about screen and television writing or writers—there wasn’t much. The closest thing I could find to a guide for writing for film or television was a classic book on playwriting I remembered from a playwriting course I took in college: The Art of Dramatic Writing, by Lajos Egri. (I still believe this book to be the best book on how to write a dramatic script; a belief, I learned when I moved to Hollywood, shared by numerous successful screenwriters.)

A few scripts found their way to me; I analyzed them the best I could. I also found some books critiquing films, and a few books by screenwriters discussing their careers. Out of all this I at least learned a little about the language of the profession, the technical terms writers and producers used.

To test out my newly formed theories about how to create a screenplay, I began my own screenplay, guided by the skimpy resources I had gathered. (It was about an emotionally damaged returning Korean War veteran and a young Indian boy who befriends him, and I managed, eventually, to get some option money for it, although it was never produced.) Once the new semester began, I tried to stay a lesson or two ahead of the class so I could anticipate their questions. It worked, well, at least some of the time.

Fortunately, I never realized how much over-my- head I was with this class until, a couple years later, I moved to Hollywood and began taking screenwriting classes from writers and directors in the profession who actually knew what they were talking about. At the time, what I taught seemed to satisfy the students and Dr. Christiansen. Some of my students even moved on to eventually work professionally in the motion picture field, and I have never received anything but grateful notes from them.

This “forced” assignment changed the course of my life. Without it, it never would have occurred to me to move to Los Angeles. I never would have gotten my job with Disney, or taught screen writing at Pepperdine University in Malibu, which helped sustain my daughter and me while I tried to build a career as a screenwriter. I never would have written or sold my "Quincy" script, which got me into the Writers Guild of America, West. I never would have written, with my partner, Pat Holmes, “Terminal Malfunction,” a TV movie Lucile Ball’s husband thought perfect for the redheaded star, and Estelle Getty liked so much she pitched it to the network herself. But all this is for a blog for another time.

NEXT TIME: ALL IS FORGIVEN—BACK IN THE DOCUMENTARY FILM BUSINESS: ASSIGNMENT BANGLADESH,

It took a couple weeks, but eventually I settled into the semester. As time passed I became more comfortable in my role as an instructor. It was fun to work with the energetic young men and women who streamed into my lab three afternoons a week to soak up what they perceived (rightly or wrongly) as the wisdom and experience I brought to the course.

They were an eager bunch, determined to learn the critical skills they needed to fulfill their dreams of becoming media stars. That is what they all wanted, you know; not just to become broadcast journalists, but stars like Connie Chung, a young TV news woman who was all the rage at the time, or Dan Rather, then one of the fair-haired boys of television news. They all knew who Rather was because he made frequent visits to the university to see his former instructor and mentor, now the head of University of Florida’s Journalism Department.

One bright-eyed young woman asked me if I thought she should take drama classes to improve her presentation skills. I am afraid I left her somewhat dismayed when I recommended instead that she pick up some courses in history and geography so she would at least know what she was talking about when she read the news on-air.

As for my private life—it was flourishing. Within a matter of weeks I found myself with a supportive circle of new friends. Someone was always asking me to dinner or inviting me to attend a get-together of some kind. One of my new friends, Joy Anderson, a children’s book author who taught children’s literature in the English Department, brought me into a group of professors from different disciplines who met once a month to gain a broader perspective of what was going on at the university. It is easy to become isolated and myopic when your time is spent exclusively with colleagues in your own discipline. A bit of inter-department pollination breeds a sharper mind, and a more content soul.

Once I felt secure in my teaching abilities, I looked to the school’s affiliated public radio and TV stations for more challenges. Dr. Christiansen assigned me the task of writing promotional announcements for both stations, a responsibility that gave me a chance to use skills I had developed early in my career when I was the Assistant Promotional Director for WCAU TV in Philadelphia. What I was really hoping for was on-air work; radio or TV, I didn’t care. However, all the spots were already filled by other faculty, and they were very protective of those assignments.

Then one day, I got my break. I had just sent Eileen off to school, placed two eggs in boiling water and was about to set the timer for four minutes, when the phone rang. It was the TV station manager.

“Sunny, can you get down to the station right away. Dr. Jacobson is sick, and we have a writer coming in in just a few minutes for an on-air interview, and no one available to do it.” I didn’t have to be asked twice. I was out the door in a flash.

I reached the studio just as we were due to go on the air; there was no time to prep for the interview. Fortunately, Dr. Jacobson had left his notes at the station and I had a chance to glance at them as I took my place. This gave me enough information to get the conversation started. I played off the author’s answers for the rest of my questions. Everyone, including the author, seemed to think the interview went well, which put me in high spirits for the rest of the day—until I spoke with my daughter.

There was a note on my desk when I returned to my office that afternoon after class: “Your daughter wants you to call her right away. She said it’s urgent!” All those instinctive fears that come with motherhood kicked in. They were exacerbated the minute I heard Eileen’s voice.

“Whoa, slow down,” I said. “What stinks?”

“The kitchen...the kitchen stinks,” she yelled into the phone. “and the whole apartment.. And there’s stuff all over the stove, and the ceiling. It’s gross! What did you do?”

At first her words didn’t compute; then it hit me. “Oh my God, the eggs! I forgot to shut off the stove.”

Eileen raved on: “And there’s a big hole in the bottom of the pot, and its stuck to the stove. It’s ruined. Everything’s ruined. You’ve got to come home right now!”

I had hoped my daughter was exaggerating—she was prone to drama—but she wasn’t. The apartment did stink. The acrid odor of sulfur hit me even before I opened the door. When the water in the pot evaporated the eggs had exploded, splattering the ceiling and wall with a malodorous hard yellow, white and brown residue. In my daughter’s words, it was “gross.” It took me two hours to clean everything up, and much longer before the unpleasant odor finally faded.

“You could have burned the place down, Mom.” Eileen was cross with me, not just because of what I did (or, actually, didn’t do), but because she was the one, not me, who came home to discover it. To save face, I insisted that she was being over-dramatic, but I knew she was right. I was lucky my carelessness had only created a mess. It could have created a tragedy.

After the egg incident things settled down again between Eileen and me, and I reclaimed my role as parent—well almost. She still occasionally confused our roles, like when I would go to spend an evening with friends and promise to be home around ten. Inevitably, at ten o’clock on the dot, no matter where I was, the phone would ring. “Has my mother left yet?” the young authoritative and slightly ‘pissed’ voice on the other end of the line would ask. It got to be a running joke among my friends. No gathering was considered complete until Eileen called.

The fall semester was about four weeks away when Dr. Christiansen called me into his office. “I have a new assignment for you,” he announced. “You will still teach the news writing lab, but a number of students have requested that we add a screenwriting course next semester, and I want you to take that class too.”

“I don’t know anything about screenwriting,” I protested.

“You write scripts for documentaries,” he said.

“Yes, but that’s not the same thing.”

“Well,” he said, “it makes you more of an authority on writing for film than any other members of the faculty, so you’ll do the class. See if you can put something together by next week.”

I had been nervous about teaching broadcast writing, but at least I had people I could turn to for help. The prospect of teaching screenwriting petrified me, particularly after Dr. Christiansen designated me the department’s prime authority on the subject. This was, remember, in the days before Syd Field and a flood of other “experts” began glutting the market with books about screenwriting.

I wrote to studios and TV stations asking if they could send me some old scripts to use for the new course. (I didn’t know about the Writers Guild of America in those days.) I scoured the library for books about screen and television writing or writers—there wasn’t much. The closest thing I could find to a guide for writing for film or television was a classic book on playwriting I remembered from a playwriting course I took in college: The Art of Dramatic Writing, by Lajos Egri. (I still believe this book to be the best book on how to write a dramatic script; a belief, I learned when I moved to Hollywood, shared by numerous successful screenwriters.)

A few scripts found their way to me; I analyzed them the best I could. I also found some books critiquing films, and a few books by screenwriters discussing their careers. Out of all this I at least learned a little about the language of the profession, the technical terms writers and producers used.

To test out my newly formed theories about how to create a screenplay, I began my own screenplay, guided by the skimpy resources I had gathered. (It was about an emotionally damaged returning Korean War veteran and a young Indian boy who befriends him, and I managed, eventually, to get some option money for it, although it was never produced.) Once the new semester began, I tried to stay a lesson or two ahead of the class so I could anticipate their questions. It worked, well, at least some of the time.

Fortunately, I never realized how much over-my- head I was with this class until, a couple years later, I moved to Hollywood and began taking screenwriting classes from writers and directors in the profession who actually knew what they were talking about. At the time, what I taught seemed to satisfy the students and Dr. Christiansen. Some of my students even moved on to eventually work professionally in the motion picture field, and I have never received anything but grateful notes from them.

This “forced” assignment changed the course of my life. Without it, it never would have occurred to me to move to Los Angeles. I never would have gotten my job with Disney, or taught screen writing at Pepperdine University in Malibu, which helped sustain my daughter and me while I tried to build a career as a screenwriter. I never would have written or sold my "Quincy" script, which got me into the Writers Guild of America, West. I never would have written, with my partner, Pat Holmes, “Terminal Malfunction,” a TV movie Lucile Ball’s husband thought perfect for the redheaded star, and Estelle Getty liked so much she pitched it to the network herself. But all this is for a blog for another time.

NEXT TIME: ALL IS FORGIVEN—BACK IN THE DOCUMENTARY FILM BUSINESS: ASSIGNMENT BANGLADESH,

Friday, July 9, 2010

THE GAINESVILLE YEARS, PART TWO

THE STRANGER WHO MOVED ME

Before heading back to Winter Haven I put a deposit down on an apartment close to the campus. When I got home I immediately tackled the challenge of moving. Since I took nothing with me when I left my husband, everything in the apartment was new, or at least newly purchased. I wasn’t about to go through furnishing another place from scratch Naively, I thought since I wouldn’t be moving far it wouldn’t cost that much.

The representative from the third moving company I called for a bid reconfirmed the bad news: No professional mover would handle the job for less than $1500. It might as well been 15 million dollars. “Thanks,” I said as I walked him to the door. “I’m just going to have to find another way to get my furniture to Gainesville.”

He looked at me thoughtfully for a moment. “Do you think you could come up with $100?” he said.

“I—I guess I could scrape up that much.”

“Look, my Buddy and I, we’ve been toying with the idea of setting up our own company. He’ got access to a free truck. We wouldn’t be competing with Beacon or anything like that. Just doing a little moonlighting locally."

“But I’m moving to Gainesville,” I reminded him.

“I know, but... well UF is playing Florida State in two weeks, and my friend and I were planning to go up there anyway. It would give us a chance to do a dry run to see how it would work. If you can move that Saturday, we could do it for $100."

I hesitated. It sounded too good to be true.

“Look at it this way,” he said, “you’d get your furniture moved, and we’d make a little traveling and drinking money for the week-end.”

I agreed to the arrangement. He gave me a piece of paper with his name (I think it was John) and phone number, said he be back around seven A.M. that Saturday morning, and left.

As promised, John and his friend showed up bright and early the morning of the “big game.” There had been a complication, he said. The free truck they had counted on wasn’t available. They had to rent a truck for the trip. “But a deal’s a deal,” John reassured me before I could panic. “I told you I would move you for $100, and that’s still the price.”

It took them a little over an hour to load the truck; I didn’t have that much stuff. “What’s wrong, Mom?” my daughter asked as the truck drove away. “You look worried.”

“I’m fine,” I told her, but there was a queasy feeling in the pit of my stomach. I had just sent two strangers off with almost everything I owned in this world. I knew John wasn’t bonded. I didn’t even know where he lived. All I had was a name and the phone number he gave me. What if this was a scam? What if it was just a way to steal my stuff? Not that I really had anything worth stealing. I shook off the idea and loaded Eileen and the few personal items I had decided to take myself into my car, and off we went to our new home.

John and his friend were waiting for us at the apartment. They were anxious to get to the game so unpacking went a lot faster than the packing. I thanked them and paid them the $100 in cash, and they were gone. Eloise was right again. The stranger came into my life, moved me to Gainesville, and then disappeared from my life. I never saw John or his friend again.

The next few weeks were tense. I enrolled Eileen in school, fixed up the apartment, and prayed that no one of color would show up before the semester started. Fortunately, my gamble paid off. The first day of the new term I was still the only applicant under consideration. Dr. Christiansen signed my contract and my academic career was officially launched. I took my place as an adjunct professor in the Broadcast Department of one of Florida’s most prestigious universities.

I had never taught before, at least not at a university, and worried about how steep my learning curve would be. The course was writing for radio and TV. Don Grooms taught the lecture part, and I was to teach the lab—the hands-on practice part of the course.

Now, for those of you who do not know me, physically, at five feet and approximately 102 pounds, I did not cut a very imposing figure. And although I was confident in my writing ability and had spent the weeks waiting for the job to be confirmed brushing up on news writing rules, I had no formal training in the subject I was about to teach, nor had I ever worked in a radio or television news room. As the students began to file into class I was truly terrified. I knew I was an imposter; the trick was not to let my students know. That’s when my acting experience came into play.

I had minored in theater in college, and worked in summer stock and Community Theater, so I decided to create a character, a new persona for my teaching role. Sunny Fader may not have had the confidence to face the students, but Professor Fader...the knowledgeable, tough, but compassionate college professor did.

That day I played the role to the hilt. I laid down the law, told the students what I expected of them, assured them if they held up their end of the bargain I would give them all the help they needed. I stood tall, spoke firmly. And, by God, it worked! The students believed I knew what I was talking about. And soon I began believing it. My student evaluations at the end of the semester were, as Dr. Christiansen reported to me, “glowing.” One of the things I had going for me, I learned from my students, was that, unlike the majority of the staff, I had real life experience. That was an important credential for them. They came to me not only for writing help, but career advice, and sometimes personal advice. And I loved working with them on all levels. To this day I love that many of my students keep in touch with me.

NEXT – BECOMING A SCREEN WRITER, THE HARD WAY

Before heading back to Winter Haven I put a deposit down on an apartment close to the campus. When I got home I immediately tackled the challenge of moving. Since I took nothing with me when I left my husband, everything in the apartment was new, or at least newly purchased. I wasn’t about to go through furnishing another place from scratch Naively, I thought since I wouldn’t be moving far it wouldn’t cost that much.

The representative from the third moving company I called for a bid reconfirmed the bad news: No professional mover would handle the job for less than $1500. It might as well been 15 million dollars. “Thanks,” I said as I walked him to the door. “I’m just going to have to find another way to get my furniture to Gainesville.”

He looked at me thoughtfully for a moment. “Do you think you could come up with $100?” he said.

“I—I guess I could scrape up that much.”

“Look, my Buddy and I, we’ve been toying with the idea of setting up our own company. He’ got access to a free truck. We wouldn’t be competing with Beacon or anything like that. Just doing a little moonlighting locally."

“But I’m moving to Gainesville,” I reminded him.

“I know, but... well UF is playing Florida State in two weeks, and my friend and I were planning to go up there anyway. It would give us a chance to do a dry run to see how it would work. If you can move that Saturday, we could do it for $100."

I hesitated. It sounded too good to be true.

“Look at it this way,” he said, “you’d get your furniture moved, and we’d make a little traveling and drinking money for the week-end.”

I agreed to the arrangement. He gave me a piece of paper with his name (I think it was John) and phone number, said he be back around seven A.M. that Saturday morning, and left.

As promised, John and his friend showed up bright and early the morning of the “big game.” There had been a complication, he said. The free truck they had counted on wasn’t available. They had to rent a truck for the trip. “But a deal’s a deal,” John reassured me before I could panic. “I told you I would move you for $100, and that’s still the price.”

It took them a little over an hour to load the truck; I didn’t have that much stuff. “What’s wrong, Mom?” my daughter asked as the truck drove away. “You look worried.”

“I’m fine,” I told her, but there was a queasy feeling in the pit of my stomach. I had just sent two strangers off with almost everything I owned in this world. I knew John wasn’t bonded. I didn’t even know where he lived. All I had was a name and the phone number he gave me. What if this was a scam? What if it was just a way to steal my stuff? Not that I really had anything worth stealing. I shook off the idea and loaded Eileen and the few personal items I had decided to take myself into my car, and off we went to our new home.

John and his friend were waiting for us at the apartment. They were anxious to get to the game so unpacking went a lot faster than the packing. I thanked them and paid them the $100 in cash, and they were gone. Eloise was right again. The stranger came into my life, moved me to Gainesville, and then disappeared from my life. I never saw John or his friend again.

The next few weeks were tense. I enrolled Eileen in school, fixed up the apartment, and prayed that no one of color would show up before the semester started. Fortunately, my gamble paid off. The first day of the new term I was still the only applicant under consideration. Dr. Christiansen signed my contract and my academic career was officially launched. I took my place as an adjunct professor in the Broadcast Department of one of Florida’s most prestigious universities.

I had never taught before, at least not at a university, and worried about how steep my learning curve would be. The course was writing for radio and TV. Don Grooms taught the lecture part, and I was to teach the lab—the hands-on practice part of the course.

Now, for those of you who do not know me, physically, at five feet and approximately 102 pounds, I did not cut a very imposing figure. And although I was confident in my writing ability and had spent the weeks waiting for the job to be confirmed brushing up on news writing rules, I had no formal training in the subject I was about to teach, nor had I ever worked in a radio or television news room. As the students began to file into class I was truly terrified. I knew I was an imposter; the trick was not to let my students know. That’s when my acting experience came into play.

I had minored in theater in college, and worked in summer stock and Community Theater, so I decided to create a character, a new persona for my teaching role. Sunny Fader may not have had the confidence to face the students, but Professor Fader...the knowledgeable, tough, but compassionate college professor did.

That day I played the role to the hilt. I laid down the law, told the students what I expected of them, assured them if they held up their end of the bargain I would give them all the help they needed. I stood tall, spoke firmly. And, by God, it worked! The students believed I knew what I was talking about. And soon I began believing it. My student evaluations at the end of the semester were, as Dr. Christiansen reported to me, “glowing.” One of the things I had going for me, I learned from my students, was that, unlike the majority of the staff, I had real life experience. That was an important credential for them. They came to me not only for writing help, but career advice, and sometimes personal advice. And I loved working with them on all levels. To this day I love that many of my students keep in touch with me.

NEXT – BECOMING A SCREEN WRITER, THE HARD WAY

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

THE GAINESVILLE YEARS

How I Got There

I suspect that everyone's life contains magic, if only one takes the time to step back and look for it. Mine certainly has. Every significant move I have made in my life, and there have been quite a few, was preceded by unexplainable events that moved me in a direction I had no idea I was going. Gainesville was no exception.

My twenty-year marriage had just undergone a slow, painful death. I had managed to derail my career as a freelance documentary writer with a "bad" decision to become a partner in a new production company. My partners were talented men. The work they produce was top quality; their ability to make sound business decisions was not. While we enjoyed considerable success with our first two projects, the company went "belly up" when we attempted to launch an under-financed television series.

The producers I had worked for in the past, miffed that I had the audacity to compete with them by becoming a partner in a production company, were not even willing to talk to me, let alone hire me. Unable to find work in my field, I tried to get a job teaching my craft. There were jobs available on the community college level, but a master's degree was required, and I didn't have one. Without the degree, my experience was considered irrelevant

And that's how, in 1974, I found myself stranded in Winter Haven, Florida, with a 12 year old daughter and no money, and no prospect of work.

I was at my wits end and feeling desperate. Then something unexplainable happened.

A few years earlier, while working for a Miami-based film company, I was sent to Daytona Beach to bid on a promotional film for the city's Chamber of Commerce. During the three day visit a young public relations man working with the Chamber showed the gathered group of film company representatives around the area so we could write our proposals. I didn't land the contract, but the young man, David, and I seemed to connect. After his formal presentations, we would sit and talk. We shared a similar perspective on life. He was younger than I was, but I learned a lot from him over those three days. David introduced me to the "Seth" books, a series of metaphysical books channeled through the writer, Jane Roberts, which have had a profound effect on the way I view life. http://www.sethlearningcenter.org/ He shared a story with me about his friend, a former ballet dancer-turned-architect, who had a massive stroke, but was so influenced by the Seth books that he defied his doctor's negative prognosis and willed himself back to a fully functioning life. Most important, David introduced me to Cassadaga.

Cassadaga, situated midway between Daytona Beach and Orlando, is a picturesque little town with narrow, oak-lined streets and quaint houses circa early 1900's. Founded 115 years ago, it is the South's oldest spiritualist community. The inhabitants are all spiritualists. For more information http://www.cassadaga.org/

I had several hours to kill between the end of my meetings in Daytona Beach on the last day of that sales trip and my flight out of Orlando. David suggested I stop by Cassadaga. He gave me directions and the name of a spiritualist he believed to be one of the most gifted in the community. I didn't intend to follow up on his suggestion; I was uncomfortable with the idea of visiting a spiritualist. But as I reached the cut-off to Cassadaga it was as if the car turned by itself. I had no trouble locating the woman David had recommended. She told me she didn't do readings in the afternoon, but when I mentioned that David had sent me, she invited me inside. My first session with a spiritualist was...well... surreal, but I came away from the meeting with a strange sense of peace, and a new understanding of a situation that had me mired down and was sucking the life out of me. What she told me rang painfully true; she spoke of things that were going on in my life that I had shared with no one. It took me a while to act on my new awareness, but I understood for the first time that day—without anger or blame—that I was in a marriage that had run its course and could not be saved.

But, back to my story.

There I was, sitting in my apartment in Winter Haven, depressed and frightened, not knowing where to turn, when my phone rang. It was David. I had not heard from him, or even though about him, since our initial encounter in Daytona Beach. It didn't occur to me to ask how he knew where to find me because the first words out of his mouth were, "I heard you are looking for work." He proceeded to tell me about a job he had been offered at the University of Florida, but was unable to take. It was with the journalism department. I started to argue that I didn't have a master's degree, but he interrupted.

"Neither do I," he said. "That didn't stop them from offering the job to me. What do you have to lose? I'll contact the head of the department and let him know you are going to call."

Now, I need to interrupt my story one last time... to relate something that had happened only a couple weeks earlier.

A friend, trying to cheer me up, talked me into making a quick trip to Cassadaga. Reluctantly, I agreed... or maybe desperately. I needed a straw to hold on to...some hope that this dark tunnel I felt l was in had a light at the other end. Unfortunately, the spiritualist I had seen last time had died. Someone suggested we try Eloise Page. We made our appointments and hoped for the best. During my reading, Eloise insisted that I was going to work at an institution of higher learning. (Remember, this was after I had just been turned down by two community colleges for a lack of credentials.) She also said this institution was north of Orlando because she could smell the pine trees, and the pine trees south of Orlando have no fragrance. Then she said that someone would help me move—a stranger I would never see again.

I came away from the session disheartened. Eloise Page's credentials had been highly touted, but nothing the woman said made any sense to me. I marked the visit off as a waste of time and money (which at the time I couldn't afford to waste).

Fast forward three weeks: I hung up the phone. David was right. What did I have to lose? I set up an appointment with the head of the journalism department at the University of Florida, and drove to Gainesville. As I walked across the campus toward the journalism building, I recalled another time, maybe ten years earlier, when, also motivated by financial problems, I accepted a job from an advertising agency for which I was not qualified. The agency needed someone to write and edit monthly employee and customer publications for two of its clients—Burger King and a construction company that built stores for Burger King and other restaurant chains. I wasn't worried about the writing part, but I had never edited a publication. I knew nothing about layout, or writing to space, or dealing with printers. (This, remember, was in the days before computers.) I needed to learn fast, so I took a week-end workshop at the University of Florida. And I remembered thinking at the time what a beautiful campus it was, and how nice it would be to teach there.

As it turned out, the job in the journalism department was for a guest lecturer a couple times a month, someone who could talk to students about real-life journalism experiences Certainly not a position with which I could support myself and my daughter. But the man who interviewed me was impressed with my documentary film experience, and told me that he had heard there was a fulltime opening in the Broadcast Journalism Department. He sent me over to the football stadium (which is where the Broadcast Journalism Department was housed in those days) to see Ken Christiansen.

My meeting with Dr. Christiansen lasted over an hour. He listened attentively as I explained my experience and credentials, which he said—in his opinion—outweighed the need for a master's degree, something he thought I could pursue while I was teaching. There was a completed job application on his desk. He was about to approve it, he said, when he was interrupted by the call from the head of the journalism department... the call about me. Dr. Christiansen picked up the application, put it in his out basket, unsigned, and offered me the position of adjunct professor. There was, however, a caveat to his offer.

The university was an equal opportunity employer, and his department had no faculty of color. If, between then and the time the new semester started, a qualified person of color applied for the job, that person would get the position.

I considered the risk. There was a good possibility that I could move to Gainesville (which I needed to do soon in order to get my daughter registered for school) only to discover that I had no job. But considering the improbability of all that had happened to get me this far—the call from a man I hardly knew that got me to the university on that particular day; arriving at Dr. Christiansen's office just as he was about to hire someone else for the position; not to mention the prediction during my visit to Cassadaga that I would be teaching at an institute of higher learning north of Orlando —I decided to take the risk. Besides, at the moment I had no other options.

NEXT TIME... the stranger who helped me move.

Tuesday, May 4, 2010

An Uncommon Man (The 5th in the series on Brazil 1972)

This is the fifth posting in a series recounting some of my experiences during a trip I made to Brazil in 1972. I was hired by the Presbyterian Church US to write and field- produce a fundraising documentary for a project the church had undertaken with a small group of Brazilian Presbyterians to rescue starving families fleeing Brazil’s drought- ravaged sertão. (See postings 4, 5, 6 & 7)

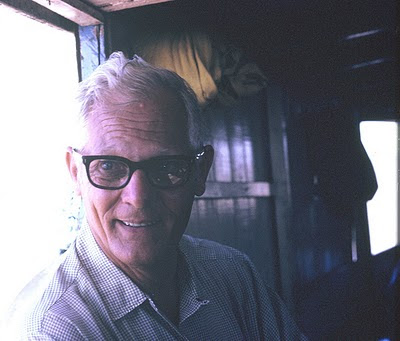

Bill Mosely was the first missionary I ever worked with. Having been reared Jewish, my only knowledge of the profession before meeting him came from reading W. Somerset Maugham’s “Rain” and books and films that tended to demonized or ridiculed the calling. So you can understand the slight trepidation I felt as I approached him for the first time that day in the Fortaleza airport. He managed to shatter my stereotyped misconceptions in a matter of minutes.

At first glance, seeing his tall, lean, slightly bent body and pale complexion, I took the man to be frail. Nothing could have been farther from the truth. Bill Mosely was, in fact, a man of unexpected physical resilience. He bounced in and out of trucks and boats with the agility of an athlete, and could sleep at the drop of a hat, waking moments later completely refreshed and ready to go. Another surprise: While deeply committed to his work, he was not, as I had anticipated, rigid or narrow, and certainly not humorless. He had a keen intellect, an active curiosity, and a wry sense of humor for which, during our time together, I seemed to provide inexhaustible fodder. Let me give you an example.

The film we were making was about how a handful of Brazilian Presbyterians, with some financial help from like-minded Christians in the United States, were helping families rescued from the drought devastated sertão get a new start in the developing area along the Amazon River. Cattle played an important part in the story—the Sindhi cattle that had been brought to Brazil from India because they could survive in an area that was often under water. Before the crew came, Bill and I scouted out a cattle ranch to arrange a “shoot” there. It was on an island which was often submerged and never completely dry. To get around one had to balance on logs laid down as a path.

During our visit, as I was trying to maneuver on one of these log paths, my foot slipped, sinking ankle-deep into a messy mixture of mud and cow paddies. (For the uninitiated, cow paddies is a polite name given to what comes out of the rear end of cattle.) Seeing my dismay, Bill suggested I go down to the river and dip my foot in to clean off the mud and “other stuff.” He waited until my foot was completely submerged and then called out, “And watch out for the Piranhas!” which extracted from me the exact panicked reflex reaction he was looking for. (Just as a point of interest, children were swimming in the river at the time unconcerned because, as I learned later, while the type of Piranhas in the area would eat chickens or cow parts, Homo sapiens are apparently not on their menu.)

Since we spent a great deal of time on the slow-moving dirt road that would eventually become the Trans Amazonian Highway... shuttling back and forth between Fortaleza and the primitive compounds in the heart of the Rain Forest, Bill and I had plenty of time to get to know each other. He may have been my first missionary, but I was his first Jew, and we were not shy in satisfying our curiosity about each other.

I learned that Bill had been in Brazil since 1945 and, as rugged as I felt the area was at the time, it was even rougher in his early years. The terrain and hostile Indians in the interior were not the only dangers he faced. Evidently the Catholic Priests saw the infidel Presbyterian Missionaries as a threat to their congregations. Bill recounted how, in the early years, it was not unusual for him to be run out of a village by stone throwing men, led by their village priest. However, that was a long time ago, he insisted; ecumenical relations were better now (1972).

How the Presbyterians came to be in Brazil is in itself an interesting tale. At least in the version of the story I got from Bill. It seems that after the Civil War, a number of Southern families, finding the idea of living in a country where Blacks were viewed to be on an equal social footing with Whites untenable, fled to Brazil. It was these expatriates, desiring spiritual guidance, who requested the Presbyterian Church send missionaries for their communities. What amused Bill most about the story was that in less than a decade, these same former Americans had begun to intermarry with the “brown” people of Brazil—the offspring of the union of European and Indian and yes...former slaves.

If I had been able to hand pick my guide during the weeks I spent in Brazil, I could not have found a more knowledgeable, companionable or enjoyable escort. When it came time to part Bill, after a slight hesitation, bent down and hugged me. With a wry smile, he shook his head and said, “It’s a shame.”

"What’s a shame?" I asked.

“You would have made a good Presbyterian,” he said.

Bill Mosely was the first missionary I ever worked with. Having been reared Jewish, my only knowledge of the profession before meeting him came from reading W. Somerset Maugham’s “Rain” and books and films that tended to demonized or ridiculed the calling. So you can understand the slight trepidation I felt as I approached him for the first time that day in the Fortaleza airport. He managed to shatter my stereotyped misconceptions in a matter of minutes.

Bill Mosely, Brazil, 1972

At first glance, seeing his tall, lean, slightly bent body and pale complexion, I took the man to be frail. Nothing could have been farther from the truth. Bill Mosely was, in fact, a man of unexpected physical resilience. He bounced in and out of trucks and boats with the agility of an athlete, and could sleep at the drop of a hat, waking moments later completely refreshed and ready to go. Another surprise: While deeply committed to his work, he was not, as I had anticipated, rigid or narrow, and certainly not humorless. He had a keen intellect, an active curiosity, and a wry sense of humor for which, during our time together, I seemed to provide inexhaustible fodder. Let me give you an example.

The film we were making was about how a handful of Brazilian Presbyterians, with some financial help from like-minded Christians in the United States, were helping families rescued from the drought devastated sertão get a new start in the developing area along the Amazon River. Cattle played an important part in the story—the Sindhi cattle that had been brought to Brazil from India because they could survive in an area that was often under water. Before the crew came, Bill and I scouted out a cattle ranch to arrange a “shoot” there. It was on an island which was often submerged and never completely dry. To get around one had to balance on logs laid down as a path.

Log path on island cattle ranch

During our visit, as I was trying to maneuver on one of these log paths, my foot slipped, sinking ankle-deep into a messy mixture of mud and cow paddies. (For the uninitiated, cow paddies is a polite name given to what comes out of the rear end of cattle.) Seeing my dismay, Bill suggested I go down to the river and dip my foot in to clean off the mud and “other stuff.” He waited until my foot was completely submerged and then called out, “And watch out for the Piranhas!” which extracted from me the exact panicked reflex reaction he was looking for. (Just as a point of interest, children were swimming in the river at the time unconcerned because, as I learned later, while the type of Piranhas in the area would eat chickens or cow parts, Homo sapiens are apparently not on their menu.)

Sindhi Cattle

Cowboys, Brazilian style

Since we spent a great deal of time on the slow-moving dirt road that would eventually become the Trans Amazonian Highway... shuttling back and forth between Fortaleza and the primitive compounds in the heart of the Rain Forest, Bill and I had plenty of time to get to know each other. He may have been my first missionary, but I was his first Jew, and we were not shy in satisfying our curiosity about each other.

I learned that Bill had been in Brazil since 1945 and, as rugged as I felt the area was at the time, it was even rougher in his early years. The terrain and hostile Indians in the interior were not the only dangers he faced. Evidently the Catholic Priests saw the infidel Presbyterian Missionaries as a threat to their congregations. Bill recounted how, in the early years, it was not unusual for him to be run out of a village by stone throwing men, led by their village priest. However, that was a long time ago, he insisted; ecumenical relations were better now (1972).

How the Presbyterians came to be in Brazil is in itself an interesting tale. At least in the version of the story I got from Bill. It seems that after the Civil War, a number of Southern families, finding the idea of living in a country where Blacks were viewed to be on an equal social footing with Whites untenable, fled to Brazil. It was these expatriates, desiring spiritual guidance, who requested the Presbyterian Church send missionaries for their communities. What amused Bill most about the story was that in less than a decade, these same former Americans had begun to intermarry with the “brown” people of Brazil—the offspring of the union of European and Indian and yes...former slaves.

If I had been able to hand pick my guide during the weeks I spent in Brazil, I could not have found a more knowledgeable, companionable or enjoyable escort. When it came time to part Bill, after a slight hesitation, bent down and hugged me. With a wry smile, he shook his head and said, “It’s a shame.”

"What’s a shame?" I asked.

“You would have made a good Presbyterian,” he said.

Thursday, April 15, 2010

Brazil - A River Adventure

This is the fourth posting in a series recounting some of my experiences during a trip I made to Brazil in 1972. I was hired by the Presbyterian Church US to write and field- produce a fundraising documentary for a project the church had undertaken with a small group of Brazilian Presbyterians to rescue starving families fleeing Brazil’s drought- ravaged sertão. (See postings 4, 5&6)

The director made a creative decision: What the film needed was a shot of the river at sunrise. Ordinarily, while inconvenient, his request would not have been a problem. We would have had an early crew call, taken a short ride to the river bank in the dark, set up our equipment, and waited for the sun to emerge.

But we’re not talking about just any river here. We’re talking about the Amazon—the widest, deepest, and, after the Nile, the longest river in the world; a river that winds for more than 4000 miles through a dense and often impenetrable tropical rain forest. One doesn’t just pop in a car and drive to this river. The only way to get the shot the director wanted was for us to spend the night aboard a boat on the river. The closest spot to get access to the Amazon and to a suitable boat was Belém.

Belém (Portuguese for Bethlehem) is a hot, humid city on the equator, about sixty miles upriver from the Atlantic Ocean. It sits on the Pará River, a part of the greater Amazon River system, separated from the larger part of the Amazon delta by Ilha de Marajó, an island the size of Switzerland. The city is actually a series of small islands intersected by channels and other rivers.

The Ver-O-Peso (Translation: Check -The-weight) Market in Belém with its four towers, is one of the largest in Brazil. It was designed and built in England and assembled in Belém. The market, seen here at the end of the dock, sells fresh fruits, plants, and fish, as well as medicinal herbs and potions, alligator and crocodile body parts, and anaconda snakes.

When we reached Belém, Bill took us to the docks near the Ver-O-Peso Market. (Bill Mosely, as you will remember, is the missionary who served as our guide and translator.) There he pointed out what he described as “a suitable boat for our journey.” I wondered what his definition of “suitable” was. Granted, the vessel was still afloat. The question in my mind was: For how long? It seemed to be held together with spit and chewing gum. And Bill’s comment about how Amazon River boats frequently capsize in heavy downpours (which there was a good chance we would encounter this time of year) did little to instill my confidence in the vessel’s seaworthiness. By this time, however, I had come to recognize that there was a bit of the devil in this man of God. Nothing seemed to delight him more than teasing me.

Our "suitable" river boat (above) and the captain/owner who took us up the river.

It was apparent that Bill had exaggerated his tale of capsizing river boats to get a rise out of us—but the sad-looking vessel in front of us certainly seemed to me like a prize candidate for disaster. However the crew, anxious to get started, quickly loaded our equipment and climbed aboard. There was nothing I could do but follow. We pushed away from the dock and began our circuitous journey to the main estuary.

My concern over our safety vanished as the lush, seductive world of the river unfolded around us. The scenery, unlike anything I had ever seen, even on this trip, hijacked my senses. Time disappeared. It is difficult to explain, but I felt caught in a deep silence, and yet there were sounds—the sounds of the boat motor, the sounds of the unseen birds and other creatures coming from somewhere behind the vivid, multi-shaded greens of the tropical rain forest that lined the shore. Then we began to see signs of human life: river houses jutting out over the water; children swimming by the river’s edge; weathered, tanned men and women on makeshift docks whose lined faces looked old and yet timeless. The camera man was in his glory.

The area at the river's edge where we traveled is known as the Varzea...because it floods during the rainy season. Over the years it has attracted more settlers because the flooding makes the soil richer and it offers a steady supply of fish, birds and turtles. The river people, a mixture of Indians, Europeans and former slaves, are known as Caboclos, Riberenos, Mestizos or Campesinos, depending on the area. They harvest wild rice and grow beans, pepper, coca, bananas and manioc (an edible tuber) which grow faster in the varzea--six monthes as opposed to the twleve months it takes in other areas of Brazil.

Finally, just as the sun was going down, we found a spot away from any signs of the river communities—a spot with the primeval feel the director was looking for—that would allow us to situate our camera perfectly to catch the sun as it rose over the lush rain forest foliage to bathe the river in morning light.

We shared our sandwiches and sodas with the boat owner and his assistant, then turned in for the night. It wasn’t long before I heard the snores of my companions. I knew Bill could sleep anywhere, in any position. When we were doing our original surveying, before the crew got there, I saw him sound asleep standing in the corner after a rough ride into the interior. And I am sure the boat owner and his helper had spent many a night on the boat. But I was surprised how easily our director, cameraman and sound engineer nodded off. As for me, I spent most of the night listening to the sounds coming from the rain forest which, for reasons I can’t explain, filled me with a peace I don’t ever remember feeling before or since.

Sometime before dawn I woke the crew. We set up our equipment by flashlight and waited for the sun. Our sound engineer, with my help, captured the awakening jungle sounds as the cameraman, assisted by the director, recorded the spectacular sunrise. Viewing the film after all these years, I see the wisdom of the director’s decision. The shot was essential. It was critical to the telling of the story, for the Amazon River is as much a character in our tale as the people whose story we were telling.

Thursday, April 1, 2010

Request for help

I am interrupting my usual storytelling to ask a favor. I have entered my new book project, "Wisdom Journey" in the "Next Top Spiritual Author Competition." To get to the second stage of the contest I need to be among the 250 contestants who receive the most votes for their project. This means that I need to get as many people as possible to go to the site and vote for my book. If you have been enjoying my blog and would like to help me turn my stories into an inspiring, empowering book, all you have to do is click the link I’ve included at the end of this explanation. It will take you right to my pitch on the contest website, which you can listen to. To vote, go to the right hand top of the page where you will see the headings: Author Login /Voter Registration/Voter Login

Click Voter Registration. Fill out the information so they can verify your email. They will send you an email confirmation and then you can go back to the site and vote. Sorry it is so complicated but they want to make sure nobody votes twice. Here’s the direct link to my page:

http://www.NextTopAuthor.com/?aid=1918

I would appreciate it if you would pass this on to anyone else you think might be willing to cast a vote for my book. Unless I am among the 250 top vote getters my book proposal will not be seen by the agents, publishers and editors who will make the final decision. This is a rare opportunity, but to take advantage of it, I need a strong support team. Thanks for helping.

________________________________________

Monday, March 15, 2010

Another Tale From Brazil

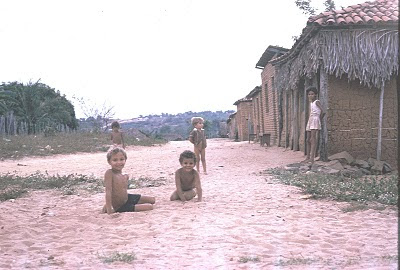

She was perfect—the little brown-skinned cabaclos girl with the golden ringlets and the sad sapphire eyes. More than half the people in Northeastern Brazil are cabaclos—descendents from a blending of the original Portuguese settlers and the country’s indigenous Indians. I guessed her to be about four, although, given the hardships of favella life, size was not always a good indicator of age. The minute I spotted her all by herself, drawing pictures in the dirt with a stick, I knew I had found my shot.

Our film was about hope, about a group of Brazilian Presbyterians who had put their faith into action. We were telling the story of how, at their own expense, these men and women were driving into the drought-plagued sertão and rescuing families facing starvation. We were showing how they nursed these refugees back to health, and then gave them a parcel of land along the Amazon and taught them how to grow their own food and raise cattle so they could support themselves. And how these rescued families were then making their own journey into the sertão to repeat the process with other suffering families.

That was our story, but the purpose of the film was to inspire its intended audience—American church goers—to reach into their pockets to help with the purchase of the parcels of land. To accomplish this, we had to establish a pressing need. That need lay in the plight of the drought’s victims. That is why I had brought my film crew to the favella. It was to the favellas of Fortaleza that many of the refugees from the sertão fled...only to find more hardships. The sad eyes of this little girl told that story in a way I knew would touch hearts.

There was more to her story. She and her mother were refugees from the sertão, but they were also outcasts in the favella because to provide for herself and her daughter, the mother had turned to prostitution. I learned this from the missionary who was working in the favella. Even among the flagelados—the beaten ones –there was a hierarchy. Women who sold their bodies, regardless of their desperate needs, were at the bottom of the social order. That is why the little girl was playing alone.

I needed to get the mother’s permission to film the little girl. The missionary came with me to translate. I watched the drawn look on the mother’s face blossom into a smile as the missionary explained. Permission was immediately granted.

By the time I retrieved my cameraman, the little girl was gone. The missionary pointed down the street. The mother was sitting on her haunches in front of the hovel that was their home, brushing the little girl’s hair. By the time I reached her, the dirt that had smudged the child’s face and soiled her arms was gone, and she was dressed in her best—and probably only dress.

Maria preparing her child for filming.

The mother beamed as she presented her daughter to me. Gone was the sad little dirt-covered waif I needed for the film. In her place was a smiling little girl who had been groomed with great love and pride.

I knew I would never use the child in the film, but I took her hand and led her to a tree where she smiled for me as the cameraman pretended to take her picture. “You have done a good thing,” the missionary said. “You have given Maria and her daughter an invaluable gift today—respect.”

And they had given me a gift. It is so easy, when you are caught up in doing “good works” to objectify the people you are seeking to help; to see only their needs, and not their humanity. That day I learned to look deeper. When I first saw Maria, I saw only an unfortunate woman deserving of my pity. Witnessing the loving care and pride with which she prepared her daughter, I saw something else: a woman whose concerns and priorities are the same as mine, a mother whose feelings for her child reach the same depths as mine. From that day on I began to see, truly see, the people I filmed. Not just their needs, but their humanity.

Our film was about hope, about a group of Brazilian Presbyterians who had put their faith into action. We were telling the story of how, at their own expense, these men and women were driving into the drought-plagued sertão and rescuing families facing starvation. We were showing how they nursed these refugees back to health, and then gave them a parcel of land along the Amazon and taught them how to grow their own food and raise cattle so they could support themselves. And how these rescued families were then making their own journey into the sertão to repeat the process with other suffering families.

Milton and Bebe, one of the couples who rescued, nursed and

taught drought victims how to survive in the Amazon

That was our story, but the purpose of the film was to inspire its intended audience—American church goers—to reach into their pockets to help with the purchase of the parcels of land. To accomplish this, we had to establish a pressing need. That need lay in the plight of the drought’s victims. That is why I had brought my film crew to the favella. It was to the favellas of Fortaleza that many of the refugees from the sertão fled...only to find more hardships. The sad eyes of this little girl told that story in a way I knew would touch hearts.

There was more to her story. She and her mother were refugees from the sertão, but they were also outcasts in the favella because to provide for herself and her daughter, the mother had turned to prostitution. I learned this from the missionary who was working in the favella. Even among the flagelados—the beaten ones –there was a hierarchy. Women who sold their bodies, regardless of their desperate needs, were at the bottom of the social order. That is why the little girl was playing alone.

I needed to get the mother’s permission to film the little girl. The missionary came with me to translate. I watched the drawn look on the mother’s face blossom into a smile as the missionary explained. Permission was immediately granted.

By the time I retrieved my cameraman, the little girl was gone. The missionary pointed down the street. The mother was sitting on her haunches in front of the hovel that was their home, brushing the little girl’s hair. By the time I reached her, the dirt that had smudged the child’s face and soiled her arms was gone, and she was dressed in her best—and probably only dress.

Maria preparing her child for filming.

The mother beamed as she presented her daughter to me. Gone was the sad little dirt-covered waif I needed for the film. In her place was a smiling little girl who had been groomed with great love and pride.

I knew I would never use the child in the film, but I took her hand and led her to a tree where she smiled for me as the cameraman pretended to take her picture. “You have done a good thing,” the missionary said. “You have given Maria and her daughter an invaluable gift today—respect.”

And they had given me a gift. It is so easy, when you are caught up in doing “good works” to objectify the people you are seeking to help; to see only their needs, and not their humanity. That day I learned to look deeper. When I first saw Maria, I saw only an unfortunate woman deserving of my pity. Witnessing the loving care and pride with which she prepared her daughter, I saw something else: a woman whose concerns and priorities are the same as mine, a mother whose feelings for her child reach the same depths as mine. From that day on I began to see, truly see, the people I filmed. Not just their needs, but their humanity.

Saturday, February 20, 2010

The Children Bury Their Own

This is the second posting in a series recounting some of my experiences during a trip I made to Brazil in 1972. I was hired by the Presbyterian Church US to write and field-produce a fundraising documentary for a project they had undertaken with a small group of Brazilian Presbyterians. That year thousands of people were dying of thirst and starvation in the semi-arid northeast section of Brazil. Many fled to Fortaleza, the closest city, only to endure more hardships. The Presbyterian project was designed to rescue some of these refugees. This posting is about something that happened while I was on a scouting trip to a favella in search of people and places to film for the documentary.

We were on our way to a favella, a collection of dilapidated shacks slapped together from tarpaper, cardboard, old shipping crates...whatever the flagelados—the beaten ones—could scavenge to create a shelter. The year was 1972. Dozens of favellas crouched in the shadows of Fortaleza’s shiny new high-rises, mocking the city’s efforts to claim its place as a modern metropolis. Overcrowded and disease-ridden, these shanty towns were the last resort for the thousands of desperate, starving men, women and children who had fled certain death in the drought-ravaged sertão. They had come to Fortaleza in hopes of finding food and work. What most of them found was more heartbreak.

The day was stiflingly hot. Dust and sand billowed up from the road under the churning of our tires, coating our windshield. “What’s that?” I asked Bill. Coming toward us, trudging along the side of the road, was a procession of barefoot children. There were about eight or nine of them ranging in age, I would guess, from three to maybe 12. One little girl was holding a crudely made wooden cross almost as big as she was. Two of the larger boys were carrying a small, oblong box that looked as if had been hammered together from the planks of a packing crate. Another child struggled under the weight of a rusted shovel.

“It’s a funeral,” Bill said. “The children are burying one of their own.” Then he told me the story.

In Brazil, at that time, infant and child mortality rates were among the highest in the world. One out of every two children died before the age of one. Half of those who survived were dead before their fifth birthday. For the children of the favellas, the odds against surviving were even greater. The biggest killer was diarrhea, a bi-product of malnutrition, poor sanitation and contaminated water.

In the favellas the death of a child had become so commonplace that parents no longer bothered to honor their passing with ceremony, so—according to Bill—in the shanty town we were on our way to visit, the children had taken it upon themselves to bury their own.

A year or so ago, he said, the children of this favella decided to provide one of their friends with a proper funeral. There was a small Catholic church down the road. They built their little coffin, hammered together a cross, and headed in procession for the church.

At first the priest told them they could not bury their friend in the church cemetery. She did not belong to the congregation. Bill didn’t know what kind of persuasion the children used, but finally the priest granted their request. But that did not satisfy the children. After they had buried their friend they knocked again on the church door. This time they asked the priest to ring the church bell to “let God know their friend was ready to come to heaven.” Again the Priest refused them, saying that the bell was only for calling people to prayer. Again, they got him to change his mind.

The procession that passed us on the road that day was headed for that little church cemetery where they would bury the small makeshift coffin, then knock on the church door and ask the priest to ring the bell to herald their friend’s entrance into heaven. We did not intrude on their solemn ceremony, but after my interviews at the favella, as we headed back to our accommodations, Bill and I stopped at the little church cemetery to pay our respects.

We were on our way to a favella, a collection of dilapidated shacks slapped together from tarpaper, cardboard, old shipping crates...whatever the flagelados—the beaten ones—could scavenge to create a shelter. The year was 1972. Dozens of favellas crouched in the shadows of Fortaleza’s shiny new high-rises, mocking the city’s efforts to claim its place as a modern metropolis. Overcrowded and disease-ridden, these shanty towns were the last resort for the thousands of desperate, starving men, women and children who had fled certain death in the drought-ravaged sertão. They had come to Fortaleza in hopes of finding food and work. What most of them found was more heartbreak.

Scenes from a favella in Fortaleza, Brazil, 1972

The day was stiflingly hot. Dust and sand billowed up from the road under the churning of our tires, coating our windshield. “What’s that?” I asked Bill. Coming toward us, trudging along the side of the road, was a procession of barefoot children. There were about eight or nine of them ranging in age, I would guess, from three to maybe 12. One little girl was holding a crudely made wooden cross almost as big as she was. Two of the larger boys were carrying a small, oblong box that looked as if had been hammered together from the planks of a packing crate. Another child struggled under the weight of a rusted shovel.

“It’s a funeral,” Bill said. “The children are burying one of their own.” Then he told me the story.

In Brazil, at that time, infant and child mortality rates were among the highest in the world. One out of every two children died before the age of one. Half of those who survived were dead before their fifth birthday. For the children of the favellas, the odds against surviving were even greater. The biggest killer was diarrhea, a bi-product of malnutrition, poor sanitation and contaminated water.

In the favellas the death of a child had become so commonplace that parents no longer bothered to honor their passing with ceremony, so—according to Bill—in the shanty town we were on our way to visit, the children had taken it upon themselves to bury their own.

A year or so ago, he said, the children of this favella decided to provide one of their friends with a proper funeral. There was a small Catholic church down the road. They built their little coffin, hammered together a cross, and headed in procession for the church.

At first the priest told them they could not bury their friend in the church cemetery. She did not belong to the congregation. Bill didn’t know what kind of persuasion the children used, but finally the priest granted their request. But that did not satisfy the children. After they had buried their friend they knocked again on the church door. This time they asked the priest to ring the church bell to “let God know their friend was ready to come to heaven.” Again the Priest refused them, saying that the bell was only for calling people to prayer. Again, they got him to change his mind.

Church cemetery where the children buried their own.

The procession that passed us on the road that day was headed for that little church cemetery where they would bury the small makeshift coffin, then knock on the church door and ask the priest to ring the bell to herald their friend’s entrance into heaven. We did not intrude on their solemn ceremony, but after my interviews at the favella, as we headed back to our accommodations, Bill and I stopped at the little church cemetery to pay our respects.

Sunday, February 7, 2010

Brazil 1972 - My First Night in Amazonia

We don’t mature in an even pattern, but rather through unexpected spurts of sudden awareness; those eureka moments when something unpredictable happens that challenges our perception of who we are and the world we inhabit. I had a series of such experiences in 1972 during an assignment in Brazil—a trip that changed the way I see myself and my world.

Fortunately, I landed in a career I enjoyed, one that enabled me to sustain my role as mother, though that did take a bit of maneuvering at times. I was feeling pretty confident about the way I was handling my life and the progress I was making in my career. When I was approached with an opportunity to go to Brazil to write and field produce a film project for the Presbyterian Church U.S. I didn’t think twice about it. Not until I was on the plane headed for Brazil.